By Deron Snyder

The accomplishments of people of color are often overlooked in American history. That is also true of social workers of color.

Lester Blackwell Granger is one such historical figure, a social worker few people know about who should enjoy wider acclaim. As Black History Month closes, it is appropriate we take a closer look at this NASW Social Work Pioneer.

Born in 1896, Granger lived during and time of tremendous upheaval and change in our nation.

He served as executive director of the National Urban League (NUL) from 1941 to 1961, presiding through World War II and the Korean War, and the birth pains of the modern civil rights movement.

Granger served in the military during World War I and experienced first-hand the racism inflicted on Black soldiers who fought for freedom abroad, only to return to home to second-class citizenship and even violence in the form of lynching.

While at the helm of NUL, Granger joined the leader of the NAACP, the Black press and others to push for desegregation of the U.S. military. The campaign lasted a decade but culminated in President Harry Truman signing Executive Order 9981 in 1948 to desegregate the military. Granger also drew up the Navy’s post-World War II integration plan and helped solve problems related to desegregation in the Navy.

For his efforts, Granger was awarded the President’s Medal of Merit by President Truman was later lauded by President Dwight Eisenhower.

Granger was leading figure in emerging social work profession

Granger attended Dartmouth College and one of his first jobs as a social worker was in New Jersey, assisting youth at a vocational school. “In fact, Granger became a leading figure in the new social work profession,” Herbert G. Ruffin II writes for blackpast.org.

The National Association of Social Workers Foundation lists Granger as one of the NASW Social Work Pioneers® because he “introduced civil rights to the social work agenda as a national and international issue.

From his Pioneers bio: “He focused attention and advocacy energy on the goal of equal opportunity and justice for all people of color, even while focusing on the condition of Black people in the United States. He is credited with leading the development of unions among black workers, as well as integrating white unions.”

Granger joined NUL in 1934 and led the organization’s Workers’ Bureau, which sought to educate and mobilize Blacks as they migrated from the rural South and sought industrial work in urban centers.

The NUL’s focus on jobs and self-help was often contrasted against the goals of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which concentrated more on ending discriminatory laws and stopping lynching of Black people.

Hugh B. Price, NUL president from 1994 to 2003, said Granger realized each aim was vital. “If you’re to function on a daily basis, you need food, clothing and shelter,” Price said. “And you want the right to vote and the right to not be lynched. All of that.”

“The Urban League’s cause was rooted in social work and helping Blacks during the Great Migration,” Price continued. “Helping them get situated when they came to town and deal with what was in their faces on a daily basis. And (scholar W.E.B.) DuBois and the NAACP were perfectly appropriate in fighting for people’s rights, etc. and etc. What you began to see with Granger – and subsequently all of the successors – was the league deal with both realities.”

Granger used role in “Black Cabinet” to push for military desegregation

Price said Granger was active with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s so-called “Black Cabinet,” an informal advisory group of Black leaders who lobbied for integration and equal access to New Deal opportunities. Not long after Granger was appointed head of the NUL in 1941, his focus shifted from unions to uniformed services.

The South didn’t have anything on the military in terms of upholding Jim Crow.

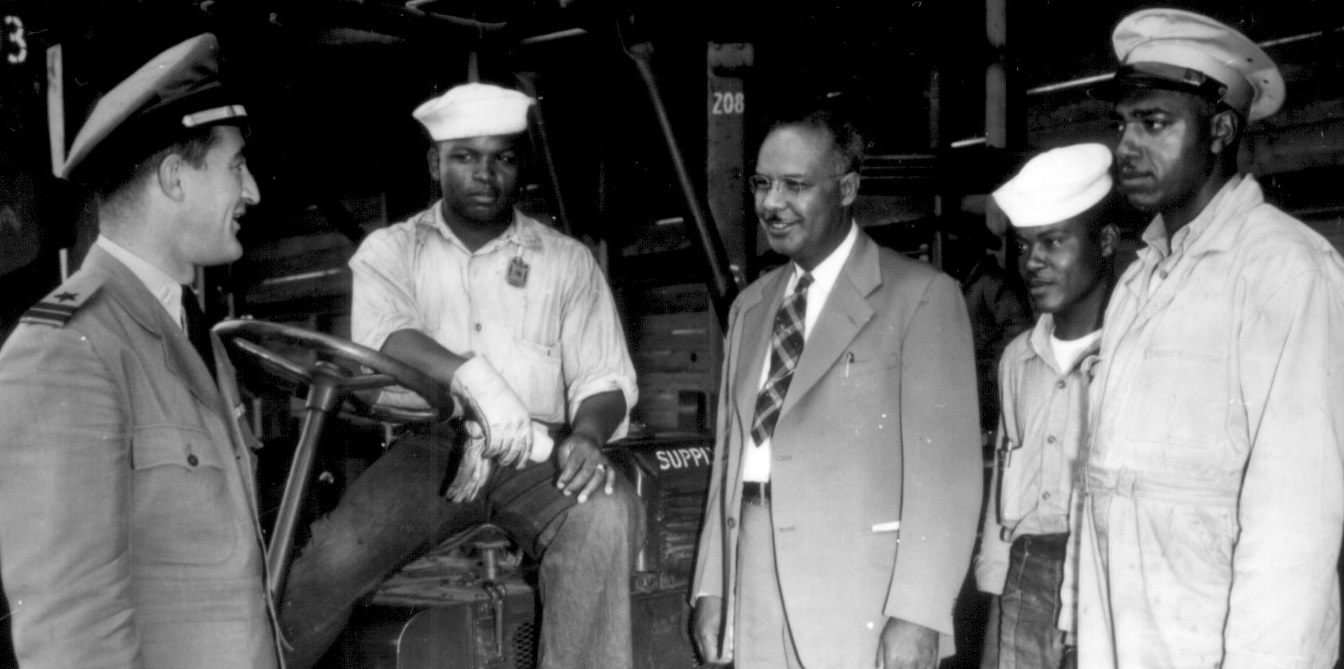

More than a million Black men and women served in the armed forces during World War II, and nearly all were assigned to segregated units commanded by white officers. Tensions were simmering when James V. Forrestal became Secretary of the Navy and shortly thereafter, in March 1945, appointed Granger as a special representative to study race relations within the branch. “In his first six months, Granger traveled 50,000 miles and visited 67 naval installations home and abroad,” Charles Wollenberg writes in the California Historical Society magazine (Spring 1979).

Granger continued to fight for military desegregation, lobbying a committee in the President Harry S. Truman administration. The executive order to desegregate the military came in 1948.

Granger was also active in the modern civil rights movement that gained momentum after the murder of Emmitt Till and the Montgomery Alabama bus boycott. By the late 1950s, Granger was discussing civil rights legislation with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Martin Luther King Jr., who led the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Granger helped educate new generation of social workers

As the NUL began fading and giving way to direct-action groups like the SCLC, Granger transitioned into a college professor who cast his vision of social work as a weapon.

He began at Dillard University, a historically Black institution, immediately upon retiring from the NUL in 1961. “We tried hard to understand his position on the civil rights movement, for he was not as militant as we thought he should be,” former student Annie Woodley Brown, DSW, writes in “Filling the Ranks,” a 2004 journal article.

Garner saw social work as a tool to complement the raging civil rights struggle, and he encouraged his students to broaden their thinking and consider the field.

“He didn’t think everybody had to do the same thing or use the same tactics in the struggle for racial equality,” Brown writes. “He wanted us to think of other ways we could contribute to the civil rights movement – participating in leadership councils, teaching in universities, managing social service organizations.”

Brown writes that Granger “really believed the profession had the potential to make a significant contribution in the area of racial, social, and economic justice.” She includes a passage of his writing in 1940 that “seemed capture the vision of social work he tried to impart on us:

“What is required … is that the social worker shall join the battle against social injustice, shall help to remake or eliminate those forces that have twisted and blighted the lives of millions of Americans in our own generation. No one is better qualified than the social worker to bring to such planning a shrewd analysis of the individual and family needs of the community: no one is more responsible for devising ways of serving these needs.”

Price said Granger brought the social work background to focus on discrimination and access to job opportunities.

“But he also moved the field and the Urban League more into advocacy and other rights issues. He’s a giant but sort of underappreciated historically, Price said. The general public might be largely unaware of Granger, but his mark on the profession continues.

Kerri Criswell, a manager with the NASW Foundation, said Granger’s dual mission of advocacy and social justice is part of the NASW Code of Ethics.

“Our Pioneers are responsible for so many things that lots of us enjoy, like social security and employment rights,” Criswell said. “They laid the groundwork and he was one of many to make a lasting impact.”

Granger’s legacy largely forgotten

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., who led the NUL from 1971 to 1981 and later became a close advisor to President Bill Clinton, bemoaned that “little attention” was paid to Granger’s death in January 1976.

Some older people vaguely recalled the name and others registered a blank, he said.

Jordan called the lack of knowledge “shameful” and stressed the importance of recalling figures who not only survived blatant racist oppression but led the fight.

“Lester Granger once defined black goals as ‘the right to work, the right to vote, the right to physical safety and the right to dignity and self-respect,’” Jordan wrote in the Oakland Post shortly after Granger died.

“The struggle for those goals is still with us and by keeping the memory of Lester Granger and the multitude of other unsung Black heroes before us, we have a better chance of fulfilling those goals.”

Deron Snyder, a native of Brooklyn, N.Y., is an award-winning journalist and Howard University graduate who lives in metro Washington, D.C.