In recent years, there has been a growing national movement to challenge the practice and premise for using solitary confinement as a method of behavioral control in the nation’s prisons, jails and juvenile facilities.The strong opposition to solitary confinement is primarily based on questions about the belief that use of such practices is a clear human rights violation.

Before we go further, let’s put the discussion in context. The history of the use of inmate solitary confinement (also known as inmate segregation) in the American correctional system goes back many years. However, more recently, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has begun to collect data on the application of such actions.

In an article entitled “Why work to reduce correctional segregation?, the Vera Institute for Justice states that since the 1980s prisons in the United States have increasingly relied on the use of segregation to manage difficult populations in their overcrowded systems. In addition, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, the number of people in restricted housing units nationwide increased from 57,591 in 1995 to 81,622 in 2005.

Social workers who practice in adult and juvenile detention facilities are well aware of a legitimate responsibility that officials have to maintain order, prevent violence and to protect vulnerable inmates from sexual and physical abuse. However, the increased use of solitary confinement can create an ethical dilemma for social workers and other service providers.

The policy of solitary confinement/segregation is not only in place in adult detention facilities, but also in juvenile facilities. It should also be noted that there are primarily two types of solitary confinement. Disciplinary (is applied as punishment when inmates break the defined prison or jail rules while administrative segregation is used when prisoners are deemed a risk to the safety of other inmates or prison staff.

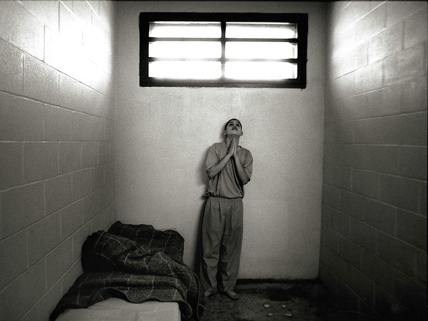

There is emerging evidence that conditions of isolation have become increasingly severe in recent years. Those conditions include super-maximum security prisons where prisoners spend years locked up 23 to 24 hours a day in small cells and “lock down” units in regular prisons where inmates similarly are isolated for 23 out of 24 hours per day with minimal human contact, exercise or access to reading materials. Research indicates solitary confinement can have a devastating impact on inmate’s mental and emotional health.

Solitary Confinement can have devastating impact on mental health

The effect is especially devastating for children and adolescents. It is estimated that up to 95,000 young people under age 18 are housed in adult prisons. Most of them are kept in “protective” segregation cells that are tantamount to prolonged solitary confinement. Juvenile justice facilities also use segregation as a disciplinary tool for rules violations.

Brain development research indicates that prolonged periods of isolation of children can have long-term traumatic impact on their emotional and social development.With respect to the relationship between mental illness and solitary confinement, it is widely known that the nation’s jails have become de facto mental health facilities. Many of the mentally ill in jails suffer from pre-existing severe mental illness. Prolonged isolation of such inmates will either trigger or exacerbate thought disorders, including delusions and hallucinations. Unmonitored segregation of the severely mentally ill also the risk of suicide.

Mental health is an area where social workers often play a significant role with federal, state, and county departments of corrections in providing assessment and treatment services. Therefore social workers have first- hand knowledge of the deleterious effect of solitary confinement and of the need for national standards for screening and monitoring mentally ill inmates placed in solitary confinement.

Social workers who practice in adult and juvenile detention facilities are well aware of a legitimate responsibility that officials have to maintain order, prevent violence and to protect vulnerable inmates from sexual and physical abuse. However, the increased use of solitary confinement can create an ethical dilemma for social workers and other service providers.

How should Social Workers Respond?

A social worker who holds a senior-level position in a large East Coast prison, who wished to remain anonymous, said a key concern is that very few prison systems in the United States actually have a social worker on staff.

“The Federal system has just recently started hiring social workers,” the social worker said. “Locally, there is one social worker for three federal facilities.”

Taking that observation at face value should give us pause knowing the need inmates subjected to solitary confinement have for assessment and treatment, especially for mental health problems. It is well known that prisons are the de facto mental health facilities. This begs the question why are we so understaffed with treatment professionals? This same social worker stated that inmates on segregation at her facility want programs, but they simply do not have the treatment staff to provide it.

There is a reality about solitary confinement from the perspective of prison/jail staff that should not be lost in this discussion. There is a need for discipline and control in prisons. When there are inmates with double and triple life sentences who then murder another inmate, what consequences should that person experience? How should we safely house a major gang leader who is the shot caller for violence against staff and other inmates, and community members?

Therefore, it seems that any approach to advocating against solitary confinement must be measured. For example, there are many from the nationwide movement against solitary confinement who feel, with a degree of justification, that solitary confinement is tantamount to torture. Those who accept this point of view will likely lean toward eliminating the practice completely. Others may not accept the torture analogy, but agree that there is a need to review how segregation is used and recommend nationally applied reforms.

In any event, the issue of the wide use of solitary confinement/segregation in our juvenile and criminal justice systems is controversial. Social workers, especially those who actually work in jails, prisons, and juvenile detention facilities, have to make individual judgments about the ethical and moral implications of solitary confinement policies that they directly witness.

What is important is that social workers should become engaged in the solitary confinement discussion so that the profession can make an informed decision about our position on the issue and how to remedy abuses in the system.

For more information contact NASW Social Justice and Human Rights Manager Mel Wilson at mwilson@naswdc.org.

For more information contact NASW Social Justice and Human Rights Manager Mel Wilson at mwilson@naswdc.org.