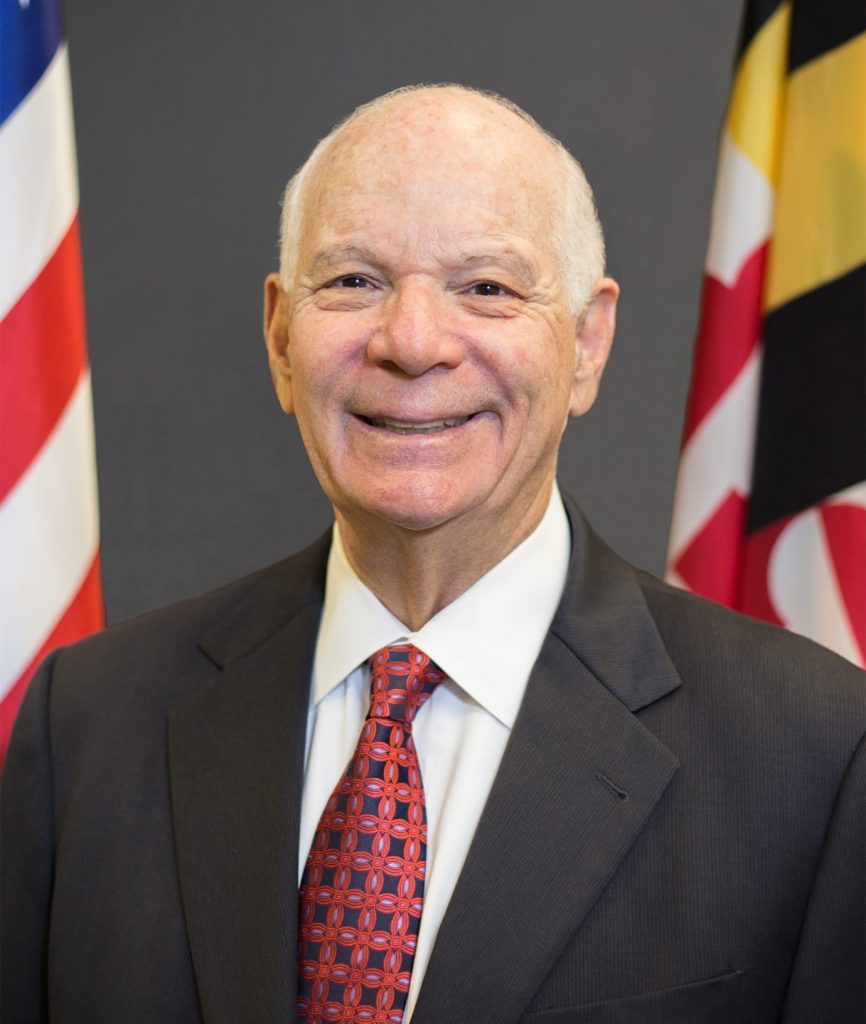

Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD) on May 18, 2023, reintroduced the Democracy Restoration Act (DRA), federal legislation that seeks to restore voting rights in federal elections to the millions of disenfranchised Americans who have been released from prison and are living in the community but are still denied the right to vote.

Cardin and his 25 or more original Senate co-sponsors must be applauded for seeking to right an egregious wrong that denies millions of Americans -disproportionately Black and Latino – the right to vote. DRA will not only address an injustice but the timing of restoring access to the ballot for those denied the right to vote comes when the country is politically and socially divided.

Their votes could play a major role in determining what political party will control the White House and Congress – not to mention the statehouses -across the country.

DRA was originally a part of the For the People Act (HR-1) that was introduced in 2021. Because Senate leadership felt DRA should be more closely aligned with the broader voting rights advocacy movement, they decided DRA should be carved out as a standalone bill.

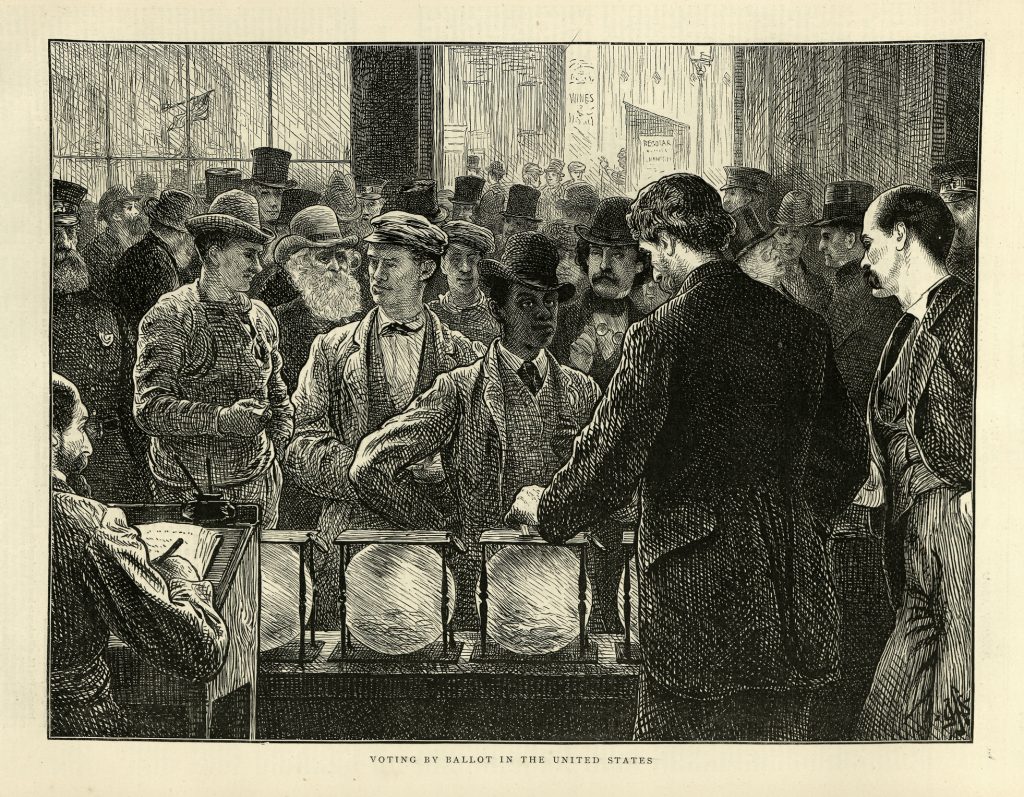

Disenfranchisement of incarcerated has long history

A Black man votes in an election in the early 1870s.

To further contextualize DRA, it should be noted disenfranchisement of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people is not new. The practice of stripping convicted felons of the right to vote goes back to the beginnings of our nation when the federal government and many states adopted felon disenfranchisement laws based on the idea that voting was a privilege for those who demonstrated “good moral character.”

However, it was the end of Reconstruction in 1877 – coinciding with the beginning of the Jim Crow Era – that ushered in the use of felony convictions as a pretext for widespread withholding of the right to vote.

During the Jim Crow Era, the highest priority for former Confederate States was to suppress the vote of newly freed slaves in defiance of the 15th Amendment.

It took nearly 90 years later, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, that the suppression of the Black vote was prohibited. Unfortunately, during that same time, the legality of felony disenfranchisement laws were specifically upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

During the past decade, advocates for voting and civil rights reforms – along with some members of Congress and state leaders – joined to end to felon disenfranchisement laws and practices.

Currently, 26 states continue to disenfranchise people after release from prison. That said, there has been some success in bringing about change.

For example, in 2020, there were approximately 5.2 million individuals disenfranchised due to felony convictions. But that number represents a close to 15 percent decline from 2016 . Additionally, with New Mexico and Minnesota recently allowing previously convicted felons to vote upon leaving prison, twenty-four states have ended felony disenfranchisement.

Those improvements aside, we cannot lose sight of the fact that racial disparities in the rate of felony disenfranchisement persist. A case in point is that one in 16 African Americans of voting age are unable to vote due to a conviction. That rate is 3.7 times greater than that of non-African Americans.

What also persists is the coupling of felony disenfranchisement with a strategic movement at the state level to propagate voter suppression laws and policies.

The connection of felony disenfranchisement and voter suppression can be seen in the use of purges of voter registration rolls as a tool for voter suppression.

To be clear, reviewing and updating voter rolls is a legitimate and necessary task. However, states that are bent on suppressing votes often conduct such purges using inaccurate data and flawed processes for maintaining voter rolls.

More to the point, they also target certain voters – such as those with felony convictions – without enforcing federally-mandated safeguards to prevent purging otherwise eligible voters.

Cardin likely timed his bill to have an impact on 2024 Election

This brings us back to why Cardin’s reintroduction of DRA is so noteworthy. Throughout his career, Cardin has been one of the Senate’s most ardent protectors of civil and human rights.

Sen. Ben Cardin

It is without a doubt that the Senator timed his re-introduction of DRA with one eye on the 2024 elections – and the critical role passage of this legislation could have in preserving our democracy. At a time when American democracy is facing its greatest threat since the Civil War, expanding access to the ballot to an otherwise fully eligible pool of voters could have immeasurable significance for the 2024 elections.

It is essential that national organizations that have long advocated for social justice offer their support and resources to proactively support the passage of DRA. In particular, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) , which supported DRA when it was introduced in 2021, must join its organizational peers in making DRA a reality.

Felony disenfranchisement is one of the most heinous and pernicious collateral consequences that impedes an individual’s ability to seek restoration, provide restitution where necessary, and be fully productive contributors to our community. – Breon Wells , CEO The Daniel Initiative.

Resources

- American Civil Liberties Union Voter Restoration

- Brennan Center for Justice

- Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

Voting Rights - Cardin Leads Renewed Effort to Restore Voting Rights to Formerly Incarcerated Individuals

- The Reentry Working Group- Voter Rights Sub-Committee

Daniel Initiative

Disclaimer: The National Association of Social Workers invites members to share their expertise and experiences through Member Voices. This blog was prepared by Mel Wilson in his personal capacity and does not necessarily reflect the view of the National Association of Social Workers.

About the Author

Mel Wilson, LCSW, MBA, is the retired Senior Policy Advisor for the National Association of Social Workers. He continues to be active on a range social policy area including youth justice, immigration, criminal justice, and drug policy. He is a co-chairperson on the Justice Roundtable’s Drug Policy Reform Working Group.